Case: SEE Change, Magazine of Social Entrepreneurship

The Global Economy has a history of operating in a profit-loss bubble, unmoved by the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) consequences of its singular focus. That bubble has been slowly thinning for more than a decade, and recently, partially due to the COVID-19 global pandemic, it has arguably burst.

Social entrepreneurs enable the adoption of eco-friendly products and services. Photo credit: Zachary Staines on Unsplash

In August of 2019, the Business Roundtable issued a statement that dethroned profit as king, overturning a 22 year-old policy that a corporation’s principal purpose is maximizing shareholder return. In its place, 181 CEOs of America’s largest corporations adopted a new Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation declaring that companies must deliver value to their customers, invest in employees, deal fairly with suppliers, and support communities in which they operate, as well as serve their shareholders.

Soon after, World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab proclaimed that business must “fully embrace stakeholder capitalism,” and announced that the theme of the 2020 Davos conference would be “Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World.” And in January of 2020, when BlackRock’s Chairman and CEO, Larry Fink, issued his annual letters to CEOs and clients, both letters highlighted a necessary focus on climate and sustainability in evaluating investments, stating that environmental and social concerns are leading to “a fundamental reshaping of finance” and “a significant reallocation of capital.”

Consumers pressure brands to act consciously

A spotlight on corporate conduct, amplified by social media, reveals consumer pressure for brands to not only provide quality products and services, but also act as good global citizens. Similarly, employees are demanding their employers act responsibly to earn their service and loyalty. As a result, it is not uncommon to hear statistics showing Unilever’s purpose-led, Sustainable Living Brands growing 69 percent faster than the rest of the business and delivering 75 percent of the company’s growth, or Patagonia’s reputation for environmental responsibility and purpose-driven mission reaping upwards of 9,000 applications per open position.

Patagonia’s reputation for sustainability has inspired its popularity. Photo credit: Jay Miller on Unsplash

Beyond external pressures to remove profit-centered blinders and take a more holistic approach to business, industry leaders are beginning to realize that the global economy requires companies to act sustainably in order to ensure any long-term profits. Agriculture companies face collapse if climate continues to degrade; energy companies will fail without alternative solutions to dwindling fossil fuels; technology relies on energy; banking relies on technology; and so on. And every industry relies on human capital, interpersonal communication, and cooperation to innovate, trade, sell, travel, etc., placing diversity, inclusion, and social sustainability among their highest priorities.

Inaction comes at great cost

It is long-past time for the global economy to catch up with social and environmental realities. Paul Polman, Unilever’s CEO from 2009 to 2019, and still a widely respected voice calling for corporate action has said, “Sadly, we have reached a moment where the cost of not acting is higher than the cost of acting.” ESGs are finally at the forefront of boardroom discussions and solutions will become more attainable with corporations supporting the charge. Businesses have reached a stage where they want to act sustainably for all the reasons listed, and more, but are often paralyzed by how to accomplish these goals.

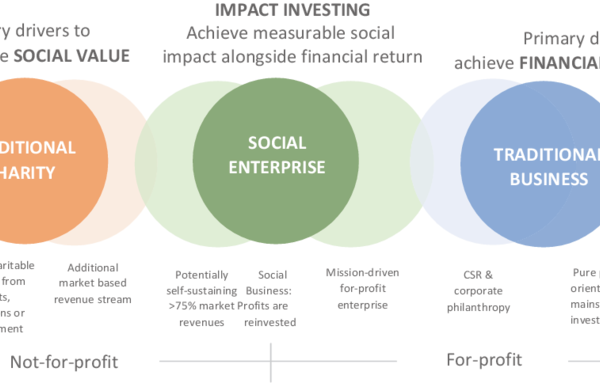

Social entrepreneurs offer a guiding light. Impact enterprises have spent decades innovating around sustainable, inclusive, and stakeholder focused ideals. They develop and iterate on new and alternative products and business models and demand ethical value chains. Their success becomes an example of what is possible, allowing larger corporations to learn and adopt sustainable practices.

A classic example of a successful social enterprise with enormous influence is TOMS shoes. TOMS set a new bar in 2006 by creating a product using environmentally responsible materials and instituting a buy one, give one policy. The practice has since become so popular that it is commonplace, with several successful companies emulating the model.

Another example of a social enterprise that paved the way for larger industry is Seventh Generation. Established in 1988, the company proved that profit was possible in eco-friendly cleaning, paper, and personal care products. Their mission is to “transform the world into a healthy, sustainable and equitable place for the next seven generations.” Its founder, Jeffery Hollender, went on to help his daughter launch another social enterprise in 2014.

Sustain Natural was the first company to produce non-toxic condoms and has since expanded to eco-friendly menstrual products. He strongly believes that, “We will never solve the myriad of complex problems we face one at a time. Social inequity produces poverty, poverty results in hunger, hunger encourages unsustainable agricultural practices that results in global climate change. Sustain is about recognizing connections, and taking on the system, not the individual problems.” Hollender’s work confirmed this market existed and it didn’t take long for larger traditional manufacturers to follow suit.

Seventh Generation proved that profit and purpose were both possible. Photo Credit: Seventh Generation

Helping social entrepreneurs achieve impact

Corporate leaders invested in sustainability know that entrepreneurs are a valuable resource and actively tap their innovation, offering support for them to explore while learning from their work. Both Unilever and IKEA operate accelerator programs focused on helping social entrepreneurs achieve greater impact. Unilever is actively “developing new business practices that grow both [their] company and communities, meeting people’s desire for more sustainable products and creating a brighter future,” while IKEA aims to, “[balance] economic growth and positive social impact with environmental protection and renewal… to meet the needs of people today without compromising the needs of future generations.” Impact organizations are leading the way.

Capacity building programs like those offered by Unilever, IKEA, and others are essential to ensuring that these pioneers have the tools they need to experiment, iterate, and perfect new ideas so that they can be adopted by the broader business community. Guidance navigating logistics, marketing, finance, and legal obligations is paramount. For instance, the Lex Mundi Pro Bono Foundation supports and empowers high impact entrepreneurs by connecting them with critical pro bono legal services. Matches ensure these organizations are advised by qualified lawyers with indigenous expertise who bring local perspective and connections, helping to explore new solutions, address challenges, find opportunities, and scale impact.

The foundation focuses on social innovators because of their enormous positive impact and influence and because their need for exceptional business legal advice aligns precisely with the defining characteristic of Lex Mundi membership. Inspired social entrepreneurs work around the world to improve education, fight disease, combat global warming, protect civil rights, and lift people out of poverty. For every grand challenge, there are dedicated social entrepreneurs working on creative solutions. They are more successful, and therefore more influential, when they have access to quality pro bono legal advice.

Social enterprises drive change in the global economy in two very important ways: (1) through the direct impact of their mission driven solutions to social and environmental challenges; and (2) by their influence on the broader business community to act responsibly. Impact organizations expand the scope of what is normal, what is possible, and what is acceptable, creating a greener and more inclusive global economy.

A version of this article was first published in The Lawyer